This post is part of a series in which I am blogging my way through a new course on partial differential equations (PDEs) that I am about to teach in two weeks. (Links to parts 1, 2, and 3.)

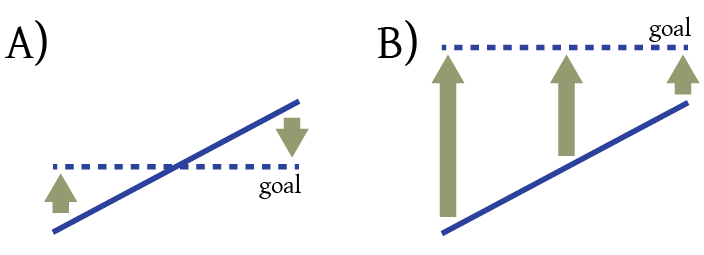

My previous post in this series was about relieving time pressure during tests. This post is about relieving time pressure on a much longer time scale.

Last semester, one of my advisees told me something that still reverberates in my head. At the time, this student was not doing well in his classes at Harvey Mudd. We were talking openly about his performance at school when he told me, “I can learn everything here at Mudd, I just feel like I learn it two weeks after the quiz or exam.”

His retelling of his challenges got me wondering about lots of things. How intentional are we about helping students become more self-aware learners? Why is so much of our education system one-size-fits-all? Why do we require students to learn things by arbitrary deadlines, anyway? Some deadlines are out of our control: the date at the end of the semester when grades have to be entered into the grade system, for example. But most of the other deadlines that I place on my students’ learning are completely arbitrary.

After some thinking, I’ve drafted the following scheme to give students more flexibility to learn at their own pace (within the confines of the semester).

First, I took my Math 180 course objectives (previously identified in part 1) and broke them up into slightly smaller learning objectives:

- Given a PDE problem, be able to categorize and characterize it with enough detail so as to be able to understand how the solution might behave and to select an appropriate solution technique

- Be able to derive PDEs from an integral conservation law, and be able to solve a first-order PDE using the method of characteristics (nonlinear PDEs may involve shocks and fans)

- Given a PDE problem over a finite domain, be able to identify whether the associated eigenvalue problem is self-adjoint and determine appropriate orthogonality conditions if it is so

- Be able to use the separation of variables technique to solve PDE problem (including using the eigenfunction expansion technique for inhomogeneous problems)

- Be able to use integral transforms (Fourier and Laplace) to solve PDE problems involving infinite or semi-infinite domains, and be able to identify how general solutions are convolutions involving Green’s functions

I think I will ask students to demonstrate their proficiency on each the five objectives above primarily through proficiency assessments (PAs)–essentially quizzes with one or two tasks that are focused on only one objective above. Students can take a PA at any time during the semester. I will try to write several identical PAs for the same objective so that a student can retake a PA until s/he is satisfied with her/his mastery of that subject. Only the highest score for each objective will remain. I will try to come up with an advanced level PA for each objective so that students who want to push themselves can do so.

Students will also demonstrate their proficiency through a comprehensive final exam worth a relatively small portion of students’ final grades (15%). It will be administered as I described in part 3.

Weekly homework assignments will also make up a small portion (10%) of students’ grades, though I will encourage them to take the assignments seriously since the majority of their learning will come about through wrestling with problems.

Each student will also create a paper or presentation (thanks to Ed Dickey’s suggestion) on an application of partial differential equations that will account for 15% of her final grade. So to summarize: proficiency assessments (60%), application project (15%), final examination (15%), homework (10%).

No doubt many of my teacher friends will see some resemblance of this scheme to Standards-Based Grading (SBG), which seems to be catching on in the K-12 world. I don’t claim that my scheme is at all original. I’ve stolen ideas from conversations with many of colleagues. (Special shout out to Dann Mallet and Charisse Farr who shared their experiences using SBG at the university level in Australia.)

My primary purpose in designing the course this way is to let students learn at their own pace. I want them to be able to take proficiency assessments whenever they feel they are ready. And if they fail one of these proficiency assessments, I want them to realize that’s not the end of the story. My advisee’s experience made me realize that when I give my students only one (or two) chances to demonstrate their proficiency, (1) the pressure to get it right leads to cramming, and (2) once the test is over they don’t care about that knowledge anymore whether they learned it or not.

A true SBG implementation would also involve getting rid of summative letter grades or numerical scores in favor of a more comprehensive description of students’ abilities and understandings. I’m still stuck with letter grades here so that’s not going to happen. I’ll have to figure out a scheme for combining scores together to create a final grade. No definite plans yet on how each PA will be scored. Many SBG implementations use a rubric scoring scheme of 0/1 to 4. Right now I’m thinking that a baseline level of proficiency should correspond to a B- somehow, since this is an intro graduate level course and I need to come up with a grading scheme that works for both undergraduate and graduate students.

In my opinion, some SBG implementations are a bit too granular in the way course objectives are defined. I remember walking into one Algebra 1 classroom recently in which the teacher had maybe 15-20 mini objectives written on the wall for the unit. The objectives were small things (as in grain size, not in importance) like “express a line in point-slope formula” and “find the y-intercept of a line”. I feel this over-granulization is why some SBG implementations overemphasize the procedural nature of mathematics.

I was very conscious of that and tried to break up my course objectives into relatively large subordinate objectives. Some of the five items above are more procedural than others, but a lot of thinking and reasoning is still involved in each. The five objectives above should be relatively decoupled from each other so that students could take them in any order. (The exception is that you probably need to master #3 before #4.) I expect most students to take them in order, however, and to pass a PA once every two or three weeks.

There is still a final exam that will assess whether students can synthesize all of the information. I’m hoping that the relatively low weight of the final exam will help alleviate anxiety about the exam. The final exam will also help my students not feel completely at sea with a weird new system.

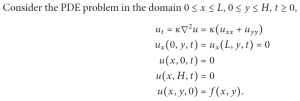

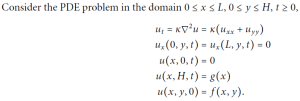

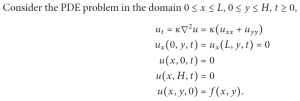

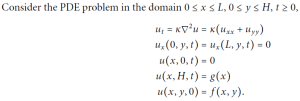

I think the biggest issue for me right now is writing all of these PAs. For each objective, I’m going to need several different but roughly equivalent mathematical tasks. That’s not an easy thing to do in PDEs. Small changes in a problem can change its complexity in large ways. For example, these problems on the surface look similar, but one is much more challenging.

Problem #1: Problem #2:

Problem #2:

Both problems involve separation of variables but problem #2 requires a change of variables first (u=v+w) where v is the solution to a Laplace equation problem also requiring separation of variables…so basically a separation of variables problem within a larger separation of variables problem.

Anyway, I’ve got lots to figure out. Your comments are appreciated!